Hi All,

Do corporations get the significance of performance and trust wrong? Let’s dive in!

(For info, the article is one of my earlier works and might differ slightly in structure.)

Performance vs Trust

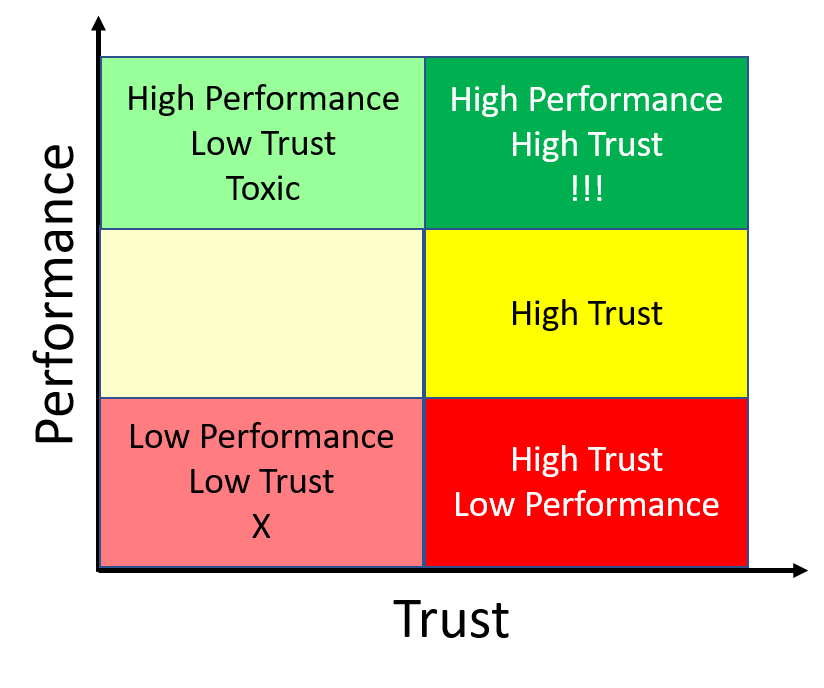

Simon Sinek (author of Start With Why) worked with Navy Seals, which are one of the highest performing teams in the world. He asked: “How do you choose the guys that make it to Seal Team 6?” Seal Team 6 is THE elite team, the best of the best. The answer he received included a chart (see above), which had ‘Performance’ on the y-axis and ‘Trust’ on the x-axis. Of course, no one wanted to pick the person who scored low on performance and low on trust, and yes, everyone prefers the person who is highly trustworthy and high performing. However, a person who scores high on performance but low in trust was considered toxic and a person who scores lower on performance but higher on trust was preferred. We are talking about the highest performing organisation out there, yet trust trumps performance when choosing who we want to work with.

Corporations often have it backwards. People are graded based on their performance while trust is expected (but not granted nearly as much significance). Yes, trust is harder to measure, however, it is a significant factor in long-term team performance.

In “The Neuroscience of Trust”, which appeared in the January 2017 Harvard Business Review, Professor Paul Zak wrote that: “Compared with people at low-trust companies, people at high-trust companies report: 74% less stress, 106% more energy at work, 50% higher productivity, 13% fewer sick days, 76% more engagement, 29% more satisfaction with their lives, 40% less burnout.”

The Science of Trust

Research has shown that, in rodents, the brain chemical oxytocin plays a crucial role in trust and determined whether they perceived another animal to be safe to approach or not, hence impacted engagement. Researcher Paul Zak wondered if this was also the case in humans. He setup the following experiment:

A participant chooses an amount of money to send to a stranger via computer, knowing that the money will triple in amount and understanding that the recipient may or may not share the profit. Therein lies the conflict: The recipient can either keep all the cash or be trustworthy and share it with the sender.

To measure oxytocin levels during the exchange, Paul’s team drew blood from people’s arms before and immediately after they made decisions to trust others (if they were senders) or to be trustworthy (if they were receivers). They found that the more money people received (denoting greater trust on the part of senders), the more oxytocin their brains produced. And the amount of oxytocin recipients produced predicted how trustworthy (i.e. how likely to share the money) they would be.

In addition, to exclude the possibility that they had observed random changes in oxytocin, the team administered doses of synthetic oxytocin (through nasal spray) to a part of the group and a placebo to the other half. They found, that giving people synthetic oxytocin more than doubled the amount of money they sent to strangers which demonstrated that oxytocin causes trust.

Now,

How do we cultivate trust?

The team continued the research and measured people’s oxytocin levels in response to various social situations and identified eight key management behaviours that stimulated oxytocin production and generate trust: (1) Recognise excellence. (2) Induce “challenge stress.” (3) Give people discretion in how they do their work. (4) Enable job crafting. (5) Share information broadly. (6) Intentionally build relationships. (7) Facilitate whole-person growth. (8) Show vulnerability.

1. Recognise excellence

Neuroscience has shown that recognition has the largest effect on trust when it occurs right after a goal has been achieved, and when it comes from peers, unexpected, personal and public. Public recognition is especially powerful as a group of people accelerate the celebration of success, and it inspires others to aim for excellence.

2. Induce “challenge stress.

When a team is given a difficult but achievable job, the moderate stress of the task releases neurochemicals (including oxytocin and adrenocorticotropin) which intensify people’s focus and strengthen social connections. Flagging here, that this only works if challenges are attainable and have a concrete end point; vague or impossible goals tend to demotivate and people are more likely to give up.

3. Give people discretion in how they do their work

It was demonstrated that, once employees have been trained, allowing them to execute tasks in their own way cultivates trust. Being trusted to figure things out is a big motivator: A 2014 Citigroup and LinkedIn survey found that nearly half of employees would give up a 20% raise for greater control over how they work!

Autonomy also promotes innovation, as different people try different approaches. Oversight and risk management procedures can help minimise negative deviations while people experiment and post-project debriefs can help share ideas across the team. Also, often younger or less experienced employees will be ‘chief innovator’ as they are less constrained by what ‘usually’ works.

4. Enable job crafting

This basically means to allow employees to move in the direction that they are most interest in. When letting people choose which projects they want to work on, people tend to focus their energies on what they care about most. As a result, employees tend to me more productive and describe their work as more rewarding.

5. Share information broadly

If employees are not well informed about their company’s goals, strategies, and tactics, this can lead to an uncertainty and stress, which inhibits the release of oxytocin and undermines teamwork.

6. Intentionally build relationships

At work, we focus primarily on completing tasks, rather than making friends. However, neuroscience experiments show that when people intentionally build social ties at work, their performance increases. A Google study similarly found that managers who “express interest in and concern for team members success and personal well-being” outperform others in the quality and quantity of their work.

7. Facilitate whole-person growth

Numerous studies show that acquiring new work skills isn’t enough; if you’re not growing as a human being, your performance is likely to suffer. High-trust companies adopt a growth mind-set when developing talent; investing in the whole person rather than just their skills has a powerful effect on engagement and retention.

8. Show vulnerability

Leaders in high-trust workplaces ask for help from colleagues instead of just telling them to do things. Asking for help is a sign of a secure leader—one who engages everyone to reach goals. Jim Whitehurst (CEO of open-source software maker Red Hat) said, “I found that being very open about the things I did not know actually had the opposite effect than I would have thought. It helped me build credibility.” Asking for help is effective because it taps into the natural human impulse to cooperate with others.

What do you think? What is your experience like?

In case of questions or thoughts you would like to share, reach me on instagram @neuroscience.musings or via the contact form on here.

Also, if you would like to support my work, here’s a way: Ko-fi.com/neurosciencemusings. If you choose to do so: Thank you!

Best regards,

Sarah

Resources:

- The Neuroscience of Trust: https://hbr.org/2017/01/the-neuroscience-of-trust

- Trust vs. Performance (Simon Sinek):http://www.teamleadershipculture.com/blog/performance-vs-trust-2/