Hi All,

This question has been central to the work of scientists for centuries; we long to understand how human beings function and try to categorise data into reliable frameworks, dimensions, and metrics. Below, we summarise fundamental starting points and cover basic psychological needs, which I believe are not just interesting but will also help us lay a foundation for future topics.

Let’s start!

Can We Break Down Human Behaviour Into Basic Principles?

We navigate a modern world with an ancient brain

For the last 100,000 years, our world has drastically changed in terms of how we organise ourselves as a society (moving from communal/tribe living to individual small families), how we work and live, and especially regarding technological progress. Yet, our (i.e., homo sapiens) brain did not change much in terms of size (since ~300,000 years), and not very much in terms of shape (since ~100,000 years).

“You can take the person out of the Stone Age, not the Stone Age out of the person.” (Abhijit Naskar)

While our brain can form new neural connections (neuroplasticity), which allows us to constantly learn, we do need to understand that our hardware is pretty ancient. Human evolution does not nearly progress as fast as other areas of life. As Professor Nigel Nicholson (Organizational Behaviour at LBS) puts it: “Our challenges may be different from hunter-gatherers, but our hardwiring is not.”

(Side note: the field of evolutionary psychology is helpful if we want to understand how seemingly ‘weird’ or counterproductive ways of human behaviour (judged by today’s standards) helped us survive in past environments.)

Our most basic motivators are Survival and Reproduction

This statement is self-explanatory and extensive at the same time – the motivators are clear, yet the way we get there might not always be linear. A few examples: humans generally thrive to be seen and accepted for who they truly are (acceptance from the group means protection = safety), we may get in fights over resources or into hierarchical disputes (status and resources are power = higher chances of survival = safety), we tend to get angry when someone crosses a boundary (self-protection = safety), and we may accept a job offer we might not want but it pays well (financial resources = safety). In this article, I won’t touch much on reproduction however, to note, mate choice and dating behaviour are highly driven by primal instincts and the goal to produce healthy offspring.

We are driven by four basic psychological needs

Just like we have basic physical needs (e.g., food, sleep, shelter), we have basic psychological needs. The framework below was first established by Professor Karl Grawe who integrated neuroscience and clinical psychology in his work and is seen as a leading scientist in the field of neuropsychotherapy. Grawe identified the following needs:

- Attachment

- Control/ Orientation

- Pleasure/ Avoidance of Pain

- Self-Enhancement

1. Attachment

The human reliance on others, our attachment to people, is one of the most basic and powerful neurobiological/ psychological needs and is present from birth.

In 1944 a (highly unethical) experiment was conducted on 40 newborn infants to determine whether humans could develop healthily with all biological/physiological needs being met, however, without affection. 20 newborn infants were housed in a special facility where caregivers ensured the babies were fed, bathed, cleaned, and had comfortable bedding. However, the caregivers were instructed not to touch, soothe, or hold the babies for longer than the completion of the above tasks required, and not to speak to them. After four months the experiment was stopped as half of the infants did not survive. The babies first stopped showing signs of self-expression (e.g., crying and facial expression changes) and eventually stopped developing and living.

Similar observations were made in US orphanages (in the 1920s), where infant mortality rates exceeded 50%, despite hygienic and safe environments. However, infants did not receive affection or soothing physical touch.

Fast forward a number of years and extensive research later, we know that affection and physical touch is imperative for healthy biological and mental development. We rely on attachment to develop a healthy immune system, regulate our nervous systems, better process physical pain, and ultimately grow into resilient and healthy adults.

As we grow older, the attachment focus naturally shifts further away from the primary caregiver and closer to the wider community. We socially evolve, nurture friendships, grow into other social circles, and form new attachments. Whether the community we grow in is based on hobbies, religion, education, or a favourite football club, what matters is that we feel a sense of belonging and acceptance.

To note, this is also why rejection hurts so much even in situations where we consciously know that it doesn’t really matter and won’t impact the trajectory of our life. If we are confronted with rejection, it does not just mean that our need for attachment isn’t met, but it is also registered in our brain as a threat to our survival. If we go back in time, the exclusion from our tribe was a death sentence as we would not have survived on our own. This fear is processed in a primal part of the brain and the feeling is hard to override with conscious thought.

Conclusion: Human beings are social beings and we are hardwired for connection.

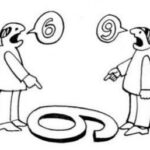

2. Control/ Orientation

Every person needs to feel that they are able to influence their own life and can take things into their own hands. We need to feel that we have an effect on the world and are not at life’s mercy.

This need is also present from birth, and while a crying child might be hard to deal with at times, crying is our only communication tool in early infancy. If the baby is being attended to and taken care of, the need for control is satisfied, and a feeling of safety is nurtured. If a baby is ignored, their stress levels rise and they experience helplessness (i.e., loss of control).

Having a sense of control is central to our mental health as we are constantly trying to navigate our environment safely. If we lose control, our body is alarmed and anxiety levels rise.

Also, taking a step back and looking at this from a bigger picture perspective: If we wouldn’t have control over our existence, why bother doing anything at all?

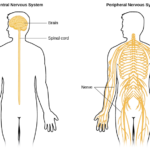

[This brings me to a random side note: Sea sponges are considered animals but do not have a brain or a nervous system. Also, they are immobile. Why do I mention this? The whole point of having a brain (and a nervous system) is to pick up stimuli from our environment (through our senses), which are then transported (through the nervous system) to our brain and processed there (i.e., the questions answered: 1) what is going on? (orientation) and 2) how shall we navigate this? (control)). Then we take action accordingly. We have a body and a system that lets us move around and take action. A sea sponge does not need a brain as they can’t do anything about their existence anyways.]

3. Pleasure/ Avoidance of Pain

This need is relatively self-explanatory: there is a basic process of evaluating what is ‘good’ and what is ‘bad’ and we are constantly trying to maximise our experiences of the ‘good’ and limit the ‘bad’.

This need is developed later in life as it requires the cognitive ability to evaluate experiences and states.

What we interpret as ‘good’ or desirable can heavily depend on individual goals. However, it is important that our perception of our current state is congruent with the intentions or goals we had set. In other words: is what we get what we wanted?

4. Self-Enhancement

Self-enhancement or self-esteem is a core human need and a significant factor when it comes to mental health. It asks the question: how worthy do I feel? What is my value in this world? The level of our self-esteem is highly subjective and forms based on opinions and beliefs about ourselves.

The need is not present from birth yet, as it requires cognitive abilities which have not been developed yet:

- It is suggested that when babies are born, they do not yet understand that they are a separate entity and perceive themselves as one with their mother. Once they learn that they are their own person, infants can develop a sense of self-awareness. For example, only then a child starts to understand that it is them when they see their reflection in a mirror.

- Babies and young children have not yet developed cognitively enough to be able to evaluate themselves. Only when they grow older, they learn to reflect on their behaviour and see themselves in comparison to others. Self-esteem is suggested to start forming around the age of 4 years old and continues to develop throughout childhood and adolescence.

It is shown that children with high self-esteem (i.e., positive perceptions of themselves) have better social and academic outcomes as they trust in themselves and believe they are worth social connection and achievement.

The topic of self-esteem is extensive and complex (from a neurobiological and psychological point of view) – for the sake of the length of this article I will leave it at that, however, given how central the topic is to our psychological wellbeing, we can potentially revisit it in a future article.

Side note: one reason why children are often very blunt and shame-free is because self-conscious emotions such as embarrassment, pride, guilt, or shame are also developed later and can only be felt once a child understands their being in relation to others.

All four basic psychological needs are interrelated

For example, if we look at how self-esteem levels may rise, one possible way is through the appreciation of others (which also feeds into closer levels of attachment). Another way might be through completing a task successfully and reaching one’s goal (which also feeds into higher levels of control).

Needs can also come into conflict with each other. For example, avoiding a promotion at work (something that would likely boost self-esteem) may be driven by a fear of leaving the current situation and relationships (need for attachment), or lack of clarity about the new job and ability to perform (need for control and orientation), or fears of failure, criticism, or too high expectation (need to avoid pain).

Side note (sorry I know there are many in this article): Psychologist Stefanie Stahl argues that the pain of heartbreak (e.g., if someone got broken up with) is fairly underestimated in society. She argues that the reason a bad breakup can influence us so negatively is that it crushes all four basic needs: the loss of a close attachment (the loss of a romantic partner), loss of control (if we are broken up with), maximum pain (what we want is not what we get), and low self-esteem (as we potentially question our worth).

How do we go about satisfying our needs? Approach vs. Avoidance

The way we approach taking care of our needs can be broken down into two motivational schemas:

- We want to move closer to something (approach; desire-driven)

- We want to move further away from something (avoidance; fear-driven)

For example, you are offered to work on a new project and you agree. Did you say ‘yes’ because you are interested in the project (approach), or did you say ‘yes’ because you don’t want to be seen as uncommitted if you say ‘no’ (avoidance)?

ANOTHER side note: Similar to needs, goals are easier to be achieved if they are approach driven. If someone wants to achieve something and they do so, it is completed and it can be crossed off the list. E.g., they want to get that promotion. On the other hand, if a goal is avoidance-driven (e.g., someone doesn’t want to be perceived as incompetent), when will they be done achieving it? Even if they are praised as highly competent in a meeting, what will the next situation bring? When setting goals, focus on approach-driven outcomes.

In Summary

Ultimately, we are constantly looking to navigate our world safely and to regulate ourselves as well as our environment to ensure our basic needs are satisfied (physically and psychologically). Personally, I enjoy this topic as it reminds me/us that we are to a large extent instinctively driven and that there are universal underlying needs in all of us.

If you enjoy the articles and would like to support my work, here’s a way: Ko-fi.com/neurosciencemusings. It’s not a requirement but if you choose to do so: Thank you!!

My Opinion

I often wonder to what extent we (i.e., the Western world) are in denial of being part of nature and not superior to it. Yes, we are high up the food chain and highly intelligent (meaning we possess qualities not seen in any other animal) however, I don’t believe that we can think ourselves out of every problem we are facing. Instead, I believe that we only reach our fullest potential by making use of our instincts (the intelligence of the body) and working with nature instead of cutting ourselves off from it. We might not make the rules of how we function but the more we learn and understand, the better we can play.

What do you think?

You can reach me on instagram @neuroscience.musings or via the contact form on here.

Enjoy your day!!

Best regards,

Sarah

Resources:

- Hess, N. (2020). Subjektive Lebensqualität in der Evaluationsforschung der gesundheitsbezogenen Sozialen Arbeit. Eine qualitative Untersuchung der dynamischen Anteile quantitativ gemessener Lebensqualitätsverläufe.

- Neubauer, S., Hublin, J. J., & Gunz, P. (2018). The evolution of modern human brain shape. Science advances, 4(1), eaao5961.

- Caspar, F., & Holtforth, M. G. (2010). Klaus Grawe: On a constant quest for a truly integrative and research-based psychotherapy.

- Podcast von Psychologin Stefanie Stahl: Sind wir wirklich so komplex? Die psychologischen Grundbeduerfnisse (July 2020)

- https://hbr.org/1998/07/how-hardwired-is-human-behavior

- Ainsworth, M. D., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books.

- Robins, R. W., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2005). Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Current directions in psychological science, 14(3), 158-162.

- https://eipmh.com/they-could-not-live-without-the-love/

- https://www.thescienceofpsychotherapy.com/consistency-theory/

- https://www.thescienceofpsychotherapy.com/basic-psychological-needs/