It can feel hard to change patterns of behaviour. For example, have you ever tried to overcome perfectionism or chronic overthinking? At times, our habits may seem irrational or even self-sabotaging to our goals. However, the human psyche and body are highly intelligent and always and reliably follow one essential principle: survival.

But what does that have to do with trauma?

In many cases, behaviours that seem misplaced or hindering today were once essential for our safety—psychologically, emotionally, or physically. These patterns often feel deeply ingrained because, in a way, today’s problems are yesterday’s solutions, originally formed to protect us.

When trauma is shown in media, it’s often portrayed as a one-off event, like a severe car accident leading to flashbacks and nightmares. While trauma can look like that, more often the consequences are subtle yet pervasive, influencing our thoughts, feelings, and behaviours without us even realising it. This invisible influence becomes our baseline, shaping how we experience life. We may notice symptoms like anxiety or chronic pain, yet may not connect them to trauma—perhaps because we were too young to consciously remember or because we don’t recognise the circumstances that affected us.

While I am glad that trauma is increasingly talked about, I have also noticed many misconceptions, especially on social media.

So, I wanted to take the time to put together a guide on the topic of trauma that aims to clarify: 1) what trauma is and how it occurs, 2) how trauma can show up in everyday life and how we can heal, 3) how some “parenting practices” damage the developing brain of children.

“Unresolved trauma impacts every level of the body-mind-soul system, shaping our sense of self and the world.” – Verena Koenig, Trauma therapist

Before we start, a reminder: If you enjoy my work, here is a way to support Neuroscience Musings via Ko-fi. If you choose to do so, thank you!

1. What is Trauma, and When Does an Experience Become Traumatic?

The word “trauma” is Greek, meaning “wound.” Trauma occurs when we are exposed to a situation that overwhelms our ability to cope. A traumatic experience is characterised by its intensity and force, which exceed our capacity to handle and process the event, leaving us feeling helpless, powerless, and under threat. Trauma is inherently linked to safety.

When we experience a traumatic event, our survival instinct kicks in, and our body takes over. Despite our highly developed conscious mind, in the face of danger, our autonomic nervous system steps in, and an instinctual, primal part of us automatically determines our reaction to ensure survival. Our bodies are always for us, not against us.

Not All Stressful Situations Are Traumatising – What’s the Difference?

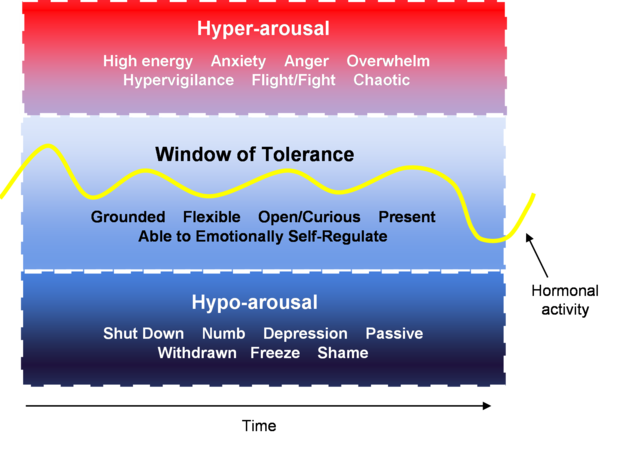

As discussed in the article on Nervous System Regulation, humans are built to handle and regulate different levels of stress i.e., physiological arousal. Sometimes we are more excited or stressed than at other times, and our bodies can accommodate these fluctuations. Following non-traumatic stress, our systems can return to a regulated state without causing long-term harm. In these cases, the body remains within what’s known as the “window of tolerance.”

What Is the Window of Tolerance?

Developed by Dr Dan Siegel, a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, the window of tolerance describes the optimal state of arousal or stimulation in which we function at our best. Within this window, we can react to and process stimuli efficiently, allowing safe fluctuations in our levels of arousal. This range enables us to learn, play, and relate well to ourselves and others.

However, outside of this range, we become dysregulated, making it difficult to process incoming stimuli. Our body’s stress responses kick-in, leading to hyper-arousal (fight/flight responses) or to hypo-aroused (e.g., freeze response, such as disassociation, numbness, or shut-down).

➡️ The width of one’s window of tolerance varies among individuals. The safer a person’s early years, the wider their window of tolerance, allowing them to “handle” more without becoming dysregulated. In contrast, disruptions during formative years narrow this window, resulting in lower tolerance to stress, where challenges can quickly feel threatening.

Trauma Is Highly Individual: What Feels Scary for One Person May Be Traumatic for Another

As we have covered, each person has different sensitivity to stress. Additionally, factors like a person’s emotional resources, their perception of control in a situation, and available social support determine how impactful an experience is. For example, if a person experiences an attack but is immediately supported emotionally and physically by someone, this support can significantly lessen the event’s long-term impact.

➡️ Trauma does not lie in the event itself but in the effects that result from an incomplete processing of it. As Gabor Mate stated, “Trauma is not what happens to you; it is what happens inside you as a result of what happens to you.”

2. Types of Traumata

Trauma is the acute or chronic loss of safety in one’s own being and in the world. It reflects a lack of inner security, creating a deep-seated loss of connection and safety.

Trauma can be divided roughly into two categories:

Acute Trauma

➡️ Also known as “mono trauma” or “type 1 trauma,” acute trauma involves a single, isolated traumatic experience with a defined start, course, and end.

These are the types of traumata most commonly thought of, like the car accident example mentioned above. An acute trauma can have a profound impact on a person. In the short term, individuals often feel shocked, numb, or in disbelief. They may experience intense grief, anger, confusion, or a blunted affect, meaning difficulty expressing emotions. These reactions and symptoms are the mind’s adaptive response to protect them from further harm.

Complex Trauma

➡️ Also called “chronic trauma,” “sequential trauma,” or “type 2 trauma,” complex trauma arises from repeated or prolonged exposure to traumatic experiences. Often occurring in childhood, chronic stress can hinder healthy development.

Causes of complex trauma include childhood abuse, military combat, or childhood neglect (see list of further causes below).

Complex trauma inflicted during formative years can be further divided into developmental trauma and attachment trauma:

- Developmental trauma: Trauma that prevents or significantly affects the healthy development of a child.

- Attachment trauma: Trauma caused by a parent or primary caregiver of the child.

Developmental and attachment trauma can overlap, such as when a parent abuses a child. However, they are not always concurrent. For instance, the death of a parent may lead to attachment trauma, but if the child is adequately supported and cared for, e.g., by close relatives, it may not necessarily result in developmental trauma.

As discussed in our article on brain development, humans, firstly, come into this world as physiologically premature, highly dependent on caregivers; secondly, the first three years of life are by far the most formative for brain development and lifelong health. In a perfect world, our parents have the capacity and resources to care for us, attune to our needs, and protect us from physical and emotional harm. If this does not happen and a child is exposed to toxic stress, their brain, neural networks, physiological responses, and neuronal metabolism may develop differently. As mentioned, we will cover the consequences of trauma next month in Part 2.

“What’s the greatest privilege on earth? Growing up with emotional support.” – Nicole LePera

3. Examples of Potential Causes of Traumata

The following are examples of potentially traumatic experiences (both acute and complex):

- Domestic violence

- Sexual abuse

- Childhood neglect (including letting babies “cry it out”)

- Accidents

- Dysfunctional family patterns (e.g., not being seen or heard, or having a parent figure deny your reality)

- Medical injury

- Intergenerational trauma (see article on Epigenetics & Generational Trauma)

- Emotional abuse

- Systemic trauma (e.g., racism, poverty, war, homelessness)

- Community violence

- (Unexpected) loss of a loved one

- Military combat

- Physical abuse

- Witnessing crime or death

- Natural disasters

4. In Essence:

➡️ Trauma is a silent force that can shape our responses, emotions, and behaviours in ways we may not consciously recognise. Whether stemming from a single event or the steady drip of chronic stress, its effects often run deeper than we realise, subtly influencing our daily lives and interactions. By understanding trauma—its origins, impact, and pathways to healing—we not only improve our own resilience but also foster compassion for others who may be carrying unseen burdens. Acknowledging trauma’s presence in our lives is the first step in breaking its hold and creating a future defined by connection, safety, and inner strength.

“The knowledge about trauma has the power to change the world.” – Verena Koenig, Trauma therapist

Do you find the topic of trauma revenant? I’m always happy to hear from you @neuroscience.musings.

Best regards,

Sarah

Resources:

- König, V. (2021). Bin ich traumatisiert? Wie wir die immer gleichen Problemschleifen verlassen. Gräfe und Unzer.

- https://apn.com/resources/fight-flight-freeze-fawn-and-flop-responses-to-trauma/

- https://uktraumacouncil.org/trauma/trauma

- https://www.gov.je/SiteCollectionDocuments/Education/ID%20The%20Window%20of%20Tolerance%2020%2006%2016.pdf